It is the only prison in Ituri, built for 100 or so prisoners, but housing five times more. The prison is dilapidated, but worse, until recently it has been a place where many prisoners die from hunger.

DRC 2010 © Claude Mahoudeau/MSF

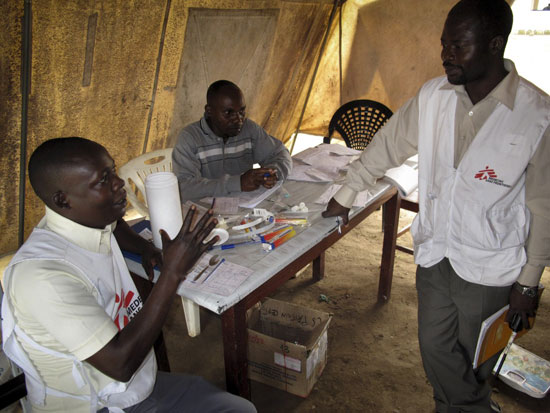

MSF staff in Bunia, from left, nurses Claude Wakungo and Serge Matata, and coordinator Manuel Ihang, stand inside the MSF medical tent situated outside of the Bunia prison where more than 500 detainees were in need of medical assistance.

Over a two-month period, 17 prisoners referred from the Bunia prison to the city’s hospital have died of severe malnutrition. The Doctors Without Borders/Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) team working in Bunia, located in the eastern district of Ituri, Democratic Republic of Congo, recently intervened to put an end to the tragedy at the prison. More than 500 prisoners are crammed into this desolate place; barely one third of them have been before a judge.

Two huge MSF tents are pitched in front of a long, crumbling building surrounded by a roll of barbed wire. In a small hut a guard sits holding open a large registry book while his two colleagues stand talking under a mango tree. This is the entrance to Bunia’s main prison. No unrest, no noticeable tension. A group of men emerges from an opening. They file neatly toward the tents. Most are young men, no different from the passers-by going about their business on the nearby street. But unlike the passers-by, these men spend their days and nights here, living in a horrible environment. It is the only prison in Ituri, built for 100 or so prisoners, but housing five times more. The prison is dilapidated, but worse, until recently it has been a place where many prisoners die from hunger.

“We had to deal with the most urgent matters first”

DRC 2010 © Claude Mahoudeau/MSF

A very ill malnourished prisoner in Bunia is now receiving treatment.

When MSF proposed a plan to the authorities to end the spate of deaths of severely malnourished prisoners they readily accepted. Since the intervention began in early December, no deaths have been reported. Nevertheless, much remains to be done in terms of improving the medical and sanitary services for the 540 people currently behind bars.

“MSF’s arrival got us out of serious problems,” said Adrien Mamoudi, assistant director of the prison. He hopes MSF’s intervention will bring to light, even at the level of his administration, the enormous hardships faced by prisoners in Bunia.

During the first week of the intervention, said project coordinator Manuel Ihanga, the team dealt with the most urgent matters first by providing ready-to-eat therapeutic food to malnourished prisoners. “As a result we were able to avoid additional deaths—that’s for sure. Fortunately, the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) quickly teamed up with MSF on this project and now supplies food to the prison on a daily basis.” The team began medical consultations the following week.

The first MSF tent houses the triage area where nurse Claude Wakungo registers patients, weighs them, takes their temperatures, and conducts simple consultations. More complicated cases, or those requiring testing, are directed to the second tent. There, Serge Matata, another nurse, conducts examinations all morning with an MSF doctor.

Jean-Pierre Tika is also a nurse, not employed by MSF, who has been working at the prison for a year. “It’s hard work,” he says. “There are many patients with many different kinds of infections. We lack the resources; we don’t have a lot of medicines. And I can’t refer those with urgent needs to the main hospital. There are too many escapes.”

A shocking sight

DRC 2010 © Claude Mahoudeau/MSF

Guards and others stand outside of the Bunia prison.

I am following Geoffrey Santini, the MSF logistician who is returning to the prison to install two water stations for the prisoners. We are barely through the doorway and I am shocked. A crowd of men of all ages are crammed into a tiny space. We enter the main courtyard, skirting bowls of cooked rice that have just arrived and are attracting hungry looks. We have to work our way through the groups of motionless men to the edge of the courtyard where the latrines and showers are located—the purpose of Geoffrey’s visit.

Crammed into a tiny space are four pit latrines and a shower block with rickety walls and no doors. The smell is revolting.

“We gave out gloves and safety equipment to prisoners so they could empty the pits,” says Geoffrey. “Before, they had to do it with their bare hands. Fortunately the ICRC is going to rebuild this sanitary block soon. For our part, we’re installing drinking water as quickly as possible.”

MSF’s swift intervention has already prompted other organizations to offer support, which encourages Manuel, the project coordinator. He enters one of the cells with me: a dark, windowless room. A total of 108 prisoners are crammed together, lying on threadbare mats on the ground. No beds. Dozens of plastic bags dangle from walls covered with scrawled inscriptions that offer a few touches of color. They are the prisoners’ only belongings. Hanging over it all is a very strong smell of sweat and other bodily fluids mingling together.

Manuel goes over to a man lying off to the side, shivering from fever. Another very young man approaches, his complexion waxen, complaining of acute diarrhea.

“We have asked the head of the prison to ask the nurse to make a round every morning in the prison to check if any were forgotten during the consultations,” says Manuel. “But it’s difficult to really know what goes on here, if we don’t come in person.”

Women and children

Another door leads us to different part of the prison and we reach the women’s and adolescents’ quarters. Some 30 women of all ages are held there together with about 20 adolescents.

“The crowded conditions can only result in violence,” said Manuel. “We’re going to try to partially resolve the problems as part of this project by suggesting a redevelopment of the site.”

One of the young men still seems to be a child. He must be barely 15 years old. Standing in front of a blackboard at the entrance to the cell, he struggled to decipher a simple phrase written in chalk: “Christmas is in two weeks. And we are here!”

“These children also need to go to school,” Manuel says in front of everyone in the room. the young man who wrote the message on the board silently agrees.

Geoffrey catches up with us, having just finished taking measurements, and assures us that water can be installed quickly. We leave the children and head for the exit, past fire pits built between a few large rocks where huge pots of rice bubble. A guard, regulation rifle on his shoulder, padlocks the iron door behind us.

“At least the prisoners aren’t hungry today, and tomorrow they’ll be able to wash,” says Manuel.