MSF is treating migrants in Italy for neglected diseases like tuberculosis and Chagas.

Italy 2011 © Mattia Insolera

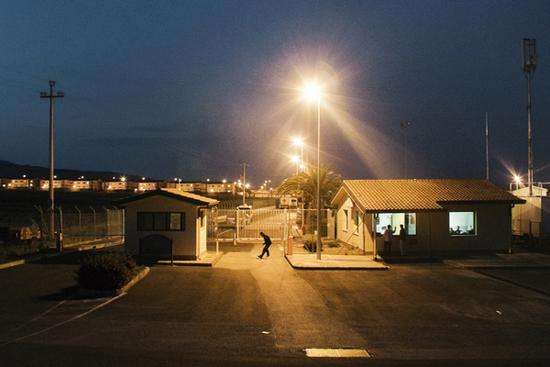

Night view of Mineo, an asylum-seeker's village where MSF provides mental health care for migrants.

Italy 2011 © Julie Remy/MSF

Dr. Sylvia Garelli

Since early 2012, more than 1,000 migrants have arrived on the tiny Italian island of Lampedusa, Sicily by boat from Libya. Doctors Without Borders/Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) is monitoring the humanitarian and medical situation and providing screening and treatment for tuberculosis and Chagas disease, two neglected diseases to which migrants are particularly vulnerable. In this interview, Dr. Silvia Garelli, MSF head of mission in Italy, discusses MSF’s activities there and the health challenges migrants face.

Are migrants still arriving on Italian shores?

The number of migrants arriving on the coast is decreasing, but there are still a few makeshift boats coming from Libya. However, nearly 1,300 refugees, migrants, and asylum seekers have been blocked by the Italian navy since the beginning of the year. No fewer than 170 migrants have lost their lives attempting the crossing, for want of effective rescue procedures at sea.

Can you describe the reception conditions in Lampedusa, Sicily?

The Italian authorities ordered the closure of the reception center in September 2011 because the migrants rioted in response to forced repatriations. Today, the reception center has been partially rehabilitated, but the port has not yet been designated a safe harbor. Medical needs are now covered by the Italian national health system, but MSF is regularly evaluating the situation and is prepared to intervene should there be a new influx of arrivals.

What is MSF currently doing to help migrants in Italy?

The conditions and health situation faced by migrants without papers in the centers for identification and expulsion continue to be extremely dire, and the situation has been aggravated by an extension of the detention period up to 18 months. Health services at these are subcontracted to private firms instead of being provided by the Ministry of Public Health, and a lack of effective coordination is causing problems that directly affect patients. For example, diseases such as tuberculosis that must be detected very early are poorly diagnosed and treated among migrants, despite the existence of national protocols. Outside of the centers, MSF has identified another medical need that primarily affects migrants (in this case, those from Latin America) and that is not covered by the national system at all: diagnosis and treatment of Chagas disease. Chagas is caused by a parasite transmitted to humans by the bite of insects especially prevalent in Latin America.

Does this mean that migrants are particularly vulnerable to infectious diseases?

Migrants are not especially more likely to be carriers of infectious diseases. However, the poor living conditions many migrants face certainly make them more vulnerable to these infectious diseases. Without standards of appropriate prevention and screening, disease can be easily transmitted within the identification and expulsion centers. "Silent" infections like Chagas are characterized by a very long incubation period during which the symptoms do not appear.

MSF has gained massive experience in the diagnosis and treatment of neglected diseases from medical projects all around the world, and we are sharing this knowledge with the health authorities in Italy and other parties involved in migrant health. In the identification and eviction centers in Caltanissetta, Milan, Rome, and Trapani, MSF works in collaboration with the Ministry of Health, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, and private entities responsible for managing the centers. An MSF mobile medical team also advises and trains medical personnel to detect and treat tuberculosis.

Chagas disease is almost unknown in Italy, so diagnosis and treatment are very limited. Symptoms may not appear for many years. At Bergamo, in collaboration with the hospital of Verona and OIKOS, an Italian NGO that deals with health care for migrants, MSF teams meet with migrants from Latin America to identify and refer people with Chagas disease. The objective of these partnerships is to improve procedures for the active detection and prevention of a disease that is often invisible, as well as to develop standard procedures for the prevention, detection and treatment of the disease that could be duplicated in other regions of the country.

In February 2011, MSF started performing medical triage of migrant, refugee, and asylum-seeking patients in the port of Lampedusa and monitoring their condition in the island’s reception center. From February to May, MSF teams made more than 1,300 medical visits, distributed 4,500 hygiene kits and blankets, and provided assistance to 17,000 migrants who had landed (over 500 women and 300 children). In 2011, an MSF team also provided mental health consultations for asylum seekers at Mineo identification center in Sicily.

Chagas disease is caused by the parasite Trypanosoma cruzi and is transmitted to humans by the bite of insects that exist mainly in Latin America. Migrants contract it in their country of origin. The parasite can also be transmitted by blood transfusion and from mother to child through the placenta. Most of those infected show no sign or symptom at the time of infection, and the symptoms don't appear for many years. In the end, chronic symptoms may develop in about one-third of those infected. Cardiac insufficiency is the most common complication, and is the cause of death among adults. Chagas disease is endemic in 21 Latin American countries, with as many as 8 to10 million cases worldwide and an annual death toll estimated at 12,500.

Tuberculosis is a contagious bacterial infection that is spread through the air. Persons who have a latent infection show no symptoms and are not contagious. However, if for some reason (such as illness) the person’s immune system is weakened, the bacteria can proliferate and symptoms start to appear. According to the World Health Organization, 5 to 10 percent of persons infected may become ill. The infection then enters its active phase. Tuberculosis may develop up to two years after infection. Today, the disease still kills nearly two million people a year worldwide and is experiencing a resurgence that has been attributed to the appearance of drug-resistant strains.