After years of declining numbers, since 2021 there has been an upsurge of cholera outbreaks around the globe, with 16 countries having declared current outbreaks. Last year, there were 735,000 reported cases of cholera worldwide, which is a 40 percent increase from 2022, while deaths rose by 80 percent. Nearly 41,000 cases and 775 deaths were reported globally in January 2024 alone, including thousands in Ethiopia, where the Somali region is the most affected.

At the same time, soaring demand and limited manufacturing capacity have resulted in a massive global shortage of the oral cholera vaccine over the last two years, creating an urgent need to adapt existing approaches to outbreak response.

What is cholera?

- Cholera is a highly contagious bacterial infection that causes cells lining the intestine to produce large amounts of fluid, resulting in diarrhea and dehydration.

- Without treatment, it can quickly lead to death by dehydration.

- Cholera spreads when someone ingests contaminated food or water.

- Access to clean water and sanitation, improved disease surveillance, community engagement, and vaccination are key to preventing cholera outbreaks.

Read more about cholera

In collaboration with Ethiopia’s Ministry of Health, Doctors Without Borders/Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) is implementing an innovative strategy known as CATI—Case Area Targeted Intervention— to respond to a cholera outbreak in Jigjiga, the capital city of the Somali region of Ethiopia. The ongoing outbreak was declared in October 2023 and has affected people across the city and surrounding areas.

Testing CATI in Ethiopia

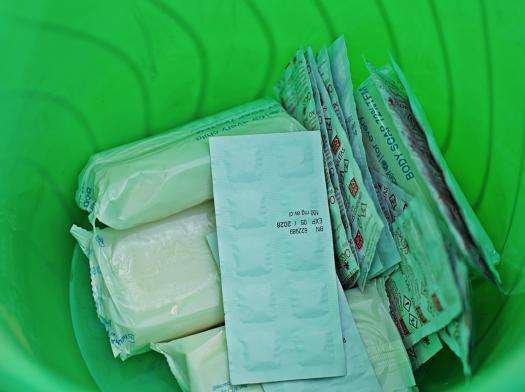

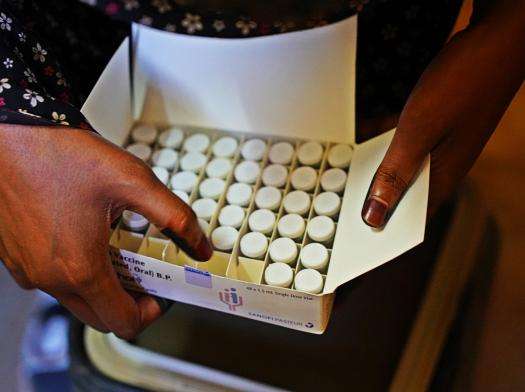

Each day, MSF teams receive a list of people diagnosed with cholera from the Regional Health Bureau. After locating where the patient lives, a dedicated team will go there and spray disinfectant throughout the 10 households closest to the patient’s home. People living in these 10 households are also given a single dose of the oral cholera vaccine, an antibiotic (doxycycline), and hygiene kits that include items such as jerry cans, water buckets, soap, and water treatment chemicals. Additionally, the CATI team does health promotion about cholera and explains where people can access care if they fall ill.

“During cholera outbreaks, people living within a 200-meter radius of an infected patient’s home are usually the most at risk of becoming infected too, and the area could become a hotspot for transmission,” said Daniel Gudina, an MSF epidemiologist in Ethiopia. “This is why we are implementing CATI in collaboration with the Regional Health Bureau here in the Somali region.”

The Somali region is the second largest in Ethiopia, with vast plains bordering Somalia, Djibouti, and Kenya. Rather than implementing a broad and resource-heavy intervention, CATI relies on extensive surveillance and the mapping of hotspot areas. Once a cholera case has been identified in the early stages of an outbreak, CATI is implemented proactively to prevent further spread of the disease. This is the first time this approach has been used in Ethiopia.

The CATI approach is different from traditional cholera response, which involves implementing interventions across a much larger geographical area to reach as much of the population as possible and requires significant resources.

Cholera outbreaks require a multidisciplinary response

In addition to rigorous case finding and conducting health promotion activities with local health authorities, MSF supported the setup and operations of a cholera treatment center at Ayerdega Health Center to provide comprehensive treatment and care for patients with severe illness.

Further, a cholera treatment unit was built at Jigjiga Primary Hospital to provide initial care and treatment for moderately ill patients, and five oral rehydration points were installed in various parts of the city. These rehydration points provide people with oral rehydration solution (a powder that is dissolved in water to treat patients with mild cholera and dehydration symptoms), improve patient access to care, and decrease the number of patients arriving at the cholera treatment center and unit.

The CATI teams are formed by both MSF and Ministry of Health staff. Each team includes:

- Staff dedicated to surveillance and data collection

- Nurses who administer vaccines

- A water, sanitation, and hygiene supervisor

- Health promoters

- Staff responsible for infection prevention and control at the cholera treatment center, cholera treatment unit, and oral rehydration points

A representative from the local neighborhood administrative unit, or kebele, is also part of the team to support community engagement.

CATI approach shows promising results

“As we have limited resources to fight the outbreak, including the provision of mass vaccination campaigns due to the shortage of vaccines, the introduction of CATI is a turning point in the region's battle against cholera,” said Ermias Amare, CATI coordinator and public health emergency officer at the health bureau of Somali region.

Between November 2023 and February 2024, MSF and the Ministry of Health treated more than 800 cholera patients, administered the limited number of oral cholera vaccines that were available to more than 8,000 people, and provided about 1,700 households with hygiene kits and health promotion information.

Though CATI is still in the trial stage in Ethiopia and requires further analysis of its ability to reduce illness and deaths in affected communities, initial results are promising. According to the Regional Health Bureau, the number of confirmed cases has decreased in all districts except for one. In this one district, the number of patients has not decreased because there is only one water source in the area, which is currently contaminated.

Inside one of the hygiene kits provided by MSF (left); a member of the CATI team prepares the oral cholera vaccine (right). Ethiopia 2024 © Mohamed Adan/MSF

Mitigating the consequences of the global vaccine shortage

Currently, all doses of the oral cholera vaccine in production until mid-March have already been allocated to affected countries, and demand for doses keeps growing, while current world reserves are at zero.

MSF has been raising the alarm about the grave consequences of this supply shortage, calling on manufacturers to urgently produce more vaccines and provide more technical support for new manufacturers to speed up regulatory processes, enabling the drastic scale-up in production that is needed to save lives.

While vaccine supply remains dismally below what is required to protect the increasing number of people living in communities at risk of a cholera outbreak, CATI is a response tool that could be used to mitigate the impact.

MSF has successfully implemented CATI in other cholera-endemic countries such as Haiti and Democratic Republic of Congo, reducing the burden of the disease.

In collaboration with Ethiopia’s Ministry of Health, MSF is compiling an impact analysis of this approach in Jigjiga. We are anticipating further partnership with the Ministry of Health to assist at-risk communities in other parts of the country.

MSF expanded its response to Kebridehar, the second-largest city in Somali region. There is also an ongoing cholera response in Lafaciise town, 40 km from Jigjiga, which MSF is supporting by training Regional Health Bureau staff on CATI implementation.

In the midst of a global cholera pandemic that started in 1961 and has not yet ended, thousands of people remain at risk of illness and death from this entirely preventable disease. Ethiopia can play a critical role in demonstrating to other countries how CATI can mitigate the consequences of the failure of global vaccine manufacturers to scale up production.

MSF continues to call for accountability for the death of our colleagues. On June 24, 2021, our colleagues María Hernández Matas, Tedros Gebremariam Gebremichael, and Yohannes Halefom Reda were brutally and intentionally killed in Tigray while clearly identified as humanitarian workers. After extensive engagement with Ethiopian authorities, we still do not have any credible answers regarding what happened to our colleagues. MSF will continue to pursue accountability for their deaths, in hopes of improving the safety of humanitarian workers in Ethiopia.