Olivier was bitten by tsetse flies carrying the sleeping sickness parasite while working deeping in the rainforest in DRC. He received treatment from the MSF team in Bili.

DRC 2013 © Stefan Dold/MSF

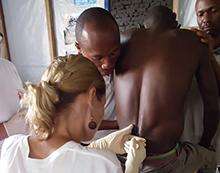

An MSF doctor performs a lumbar puncture on Olivier to determine whether sleeping sickness parasites have progressed to his central nervous system.

Bitten by tsetse flies when he worked deep in the rainforest, father-of-three Olivier gets a wake-up call when Doctors Without Borders/Médecins Sans Frontères (MSF)’s mobile sleeping sickness team comes to his home town of Bili, in Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC).

Olivier sits on a wooden stool with his arms wrapped protectively around his head. One nurse supports him from the front, another from the side. The syringe enters his lower back directly above the spine.

“You have to locate the syringe between the third and fifth lumbar vertebrae,” says Dr. Katharina Totz of MSF’s mobile sleeping sickness team in DRC, as she pushes the syringe in until a drop of cerebrospinal fluid can be seen. “You have to disinfect the skin thoroughly and work with sterile instruments,” she says, “but apart from that a lumbar puncture is not very complicated.”

For patients with sleeping sickness, which is also known as Human African Trypanosomiasis, or HAT, a lumbar puncture is necessary to diagnose how far the disease’s parasites have advanced. Are they just in the blood, or have they progressed to the central nervous system? Without treatment, a person whose nervous system is under attack by the disease will suffer sleeping disorders, become disorientated, and eventually die.

“When the syringe pierced my skin, it hurt a bit—but otherwise it wasn’t too bad,” says Olivier. It is the first day of MSF´s sleeping sickness project in Bili hospital, in the far north of the country, and Olivier has come to get himself tested. “I often have a headache and feel sleepy,” says Olivier. “When the MSF team announced in the marketplace what they were doing here, I said to myself that I should get tested as soon as possible.”

Olivier lives in Bili town, but has spent a lot of time in the surrounding forests, where the flies that transmit the parasites are found. “I roved around the jungle for several months working as a cook for a team of environmentalists who were filming chimpanzees,” says Olivier. “I often go hunting or fishing in the forest, too. I have been bitten by tsetse flies quite a few times.”

When Olivier arrived at Bili hospital, the process of testing him for the disease began. “Unfortunately the diagnosis of sleeping sickness is very complicated,” says Dr. Totz.

She began by taking a drop of blood from Olivier´s fingertip. When mixed with a reagent, which must be kept permanently cool, and after some minutes in a rotator, his blood showed clear signs of the antibodies that indicate the presence of sleeping sickness parasites.

“Under the microscope, we couldn’t find the parasites in his blood serum. But we verified a high number of antibodies, even in highly diluted blood,” says Dr. Totz. “In a region like Bili, where sleeping sickness is widespread, we treat patients like Olivier even if we cannot detect the parasites with absolute certainty.”

Dr. Totz went on to examine Olivier’s lymph nodes, took a blood sample for further tests, and carried out the lumbar puncture to get a sample of cerebrospinal fluid. If the results show that the disease is still in the early stages, Olivier will need to come to the hospital for an injection each day for a week. If the disease has advanced to his nervous system, he will be admitted to hospital for ten days to receive nifurtimox-eflornithine combination therapy (NECT), a cocktail of pills and injections.

Although the combination therapy will cure Olivier, it is not an efficient way of fighting the disease, says Dr. Totz. “Olivier’s case shows clearly that we need one drug for both phases of the disease which can be easily administered,” she says. “If this was the case, a lumbar puncture would not be necessary, neither would a hospital stay—we could just have given him pills for two weeks.”

The existence of a simple, reliable test would also make it much easier to diagnose cases of sleeping sickness and get a step closer to eliminating the disease. “If even nurses in remote health posts could treat sleeping sickness,” says Dr. Totz, “then the disease could be pushed back much more efficiently. But, unfortunately, that is not a priority for pharmaceutical companies.”

There is some reason for hope: the Drugs for Neglected Diseases initiative (DNDi), a network co-founded by MSF, is preparing a study with an improved drug in the Bili area. But it will be too late for Olivier, who has just heard he will need to come back to the hospital the following week for a second lumbar puncture after the sample was contaminated by a drop of blood that prevented a definite diagnosis.

Despite the prospect of another needle in his spine, Olivier is relieved that MSF is working in Bili. ”What would I have done otherwise?” he asks. “Who would have treated me? It is very important—for me personally, but also for the whole community—that MSF has come to Bili.”