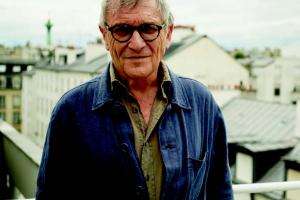

Rony Brauman, a French medical doctor who specializes in tropical medicine and epidemiology, has worked with Doctors Without Borders/Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) since 1978 and served as the organization’s president from 1982 to 1994. As one of MSF’s earliest members, Brauman helped to establish many of the medical and logistical protocols our teams still use today.

In the early and mid-1980s, not long after I had started working with MSF, there were five “hotspots” in the world where conflict and instability had resulted in massive population displacements: Southeast Asia, Central America, Southern Africa, the Horn of Africa, and Central Asia. From 1976 to 1982, there was a massive increase in the number of people displaced worldwide.

If you look at the map of MSF’s work during that time you will see that most of our programs were in those five regions, most of them in refugee camps. It was our ambition to be present in any place where there were refugees in need of medical assistance, and at the time two-thirds of the world’s refugees were living in refugee camps.

We also crossed borders unofficially in order to start programs in areas controlled by armed groups, from Pakistan to Afghanistan; Sudan to Eritrea, Tigray, and Chad; from Zaire to Angola; from Honduras to El Salvador.

In a way, MSF was one of the first nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) to realize the importance of getting involved in those camps. Previously, aid organizations focused heavily on development. It was widely believed that the way to address medical issues was through social betterment—improved living conditions, income, hygiene, et cetera. Doctors were considered a bit like missionaries, like a priest or a soldier, and were not prioritized by NGOs. These critiques and concerns were irrelevant in these new settings.

In 1980, a year and a half after the Khmer Rouge regime [in Cambodia] was toppled by the Vietnamese army, there was an influx of tens of thousands of refugees who crossed the Thai border in a terrible state. Malnutrition, parasites, malaria—it was a nightmare, and we were really overwhelmed. Because no one had ever done this kind of work at this kind of scale, we made many mistakes. We had needles, but they were not compatible with the threads on the syringes. We had drugs that were absolutely useless. It was improvised in the worst sense of the word.

But we built our knowledge, developed our public health approach incorporating nutrition, immunization, and water and sanitation, in addition to inpatient departments and pharmacies. It took us months to put all these in place, but it happened. Little by little things improved, and we eventually became experts in the management of [health care in] refugee camps. In many places, we provided health services to people living in the surrounding areas as well, something that is now standard MSF procedure.

Aurélie Ponthieu has worked with MSF since 2006 and currently leads the forced migration team in our analysis department. Her research and writing helps to inform MSF’s humanitarian action and advocacy around the world.

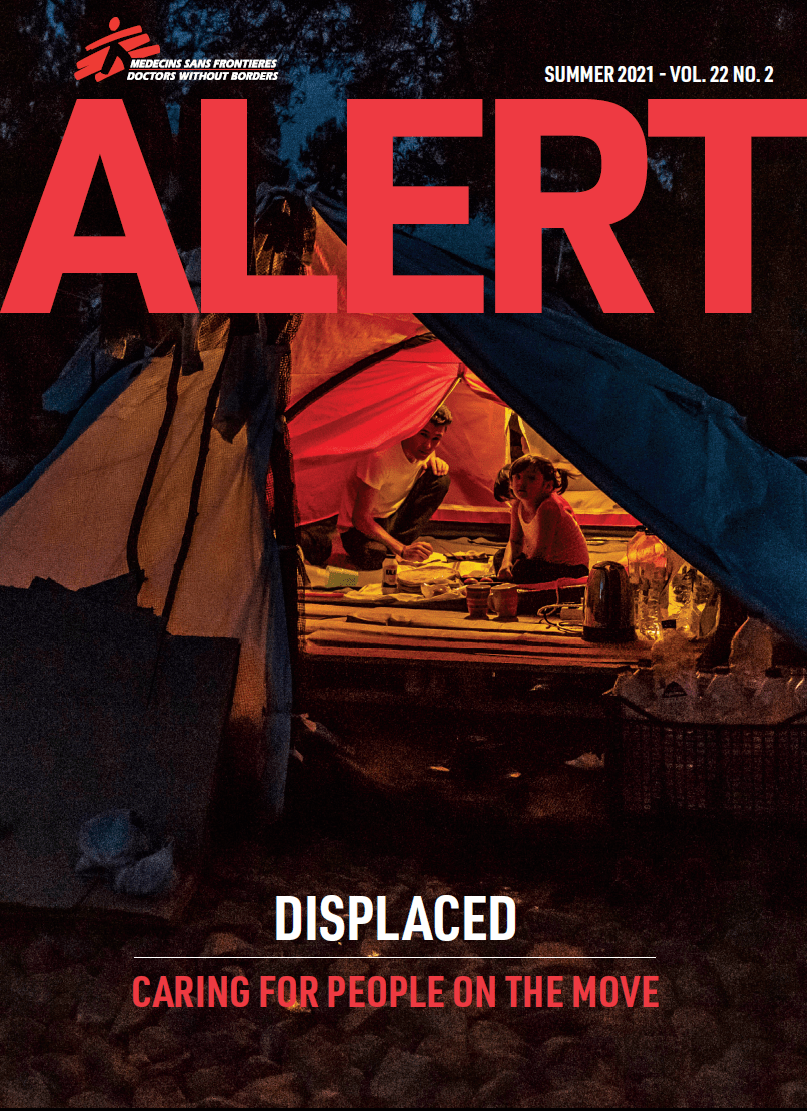

When it comes to providing medical care to refugees and other displaced people, the challenges today are different than they were in the early 2000s and before. There are now fewer large refugee camps in the world, but the people who wind up living in them are staying there for much longer than they once did. But at the same time there is growing mobility, and the majority of the world’s displaced people are in urban settings, not in refugee camps.

MSF has had to adapt to this new reality. We still have significant projects in camps in places like Dadaab, Kenya, and in South Sudan, but increasingly we must help refugees and other displaced people in the hostile, challenging urban environments where most of them now are.

MSF must be able to work on both fronts: In the more “traditional” humanitarian environments like in South Sudan—where people are displaced in areas where there are no resources to welcome them, access to health care is limited, and there are a lot of health risks like disease outbreaks—and in places where mortality rates might be lower but there are still massive needs, especially in terms of mental health and trauma, like at the US-Mexico border or detention centers on the Greek islands.

MSF must also be ready to respond to growing numbers of people displaced by the effects of climate change. It’s a key challenge, and I don't think we have the full understanding yet of how it is already affecting people on the move today. It’s sometimes difficult to quantify—when you lose everything, you don't say, “Oh, I fled home because of climate change.” That's not how people phrase the reasons that push them to cross borders.

But we know it’s a serious and growing issue, so we’re advocating for states to extend protections for displaced people instead of continuing to tighten borders.