Fifty-seven-year-old Ahmed* is angry when he retells the story of how he and his family arrived in Pulka—a small town in the Gwoza region of southern Borno state in northeastern Nigeria. But his face lights up with a smile as he remembers his life back home in the nearby village of Kirawa before the conflict between the Nigerian government and Boko Haram began.

Ahmed reaches into his pocket and produces four identification cards. One card belongs to his wife, another shows his membership to a political party that no longer exists, while the other two identify him as a member of two farmers associations.

For Ahmed, it means a great deal to be officially recognized as a farmer. “I could farm up to 20 bags of grain a year in Kirawa,” he says with a smile. “I farmed guinea corn, maize, onions, tomatoes, and other crops. We were farming all through the year, during both the rainy and dry seasons.”

But that was before the conflict forced Ahmed and his family to flee across the border to Cameroon; the two countries are separated by a river. Ahmed lived in Cameroon for a year before returning to Nigeria after what he referred to as constant harassment by Cameroonian soldiers telling him and others who had fled Nigeria to go back to their fatherland.

Pushed back into conflict

“They kept pushing us to leave. In such a situation, what were we to do? We had heard that other Nigerians in other places were being loaded in trucks and taken away and we did not want to wait for that to happen,” says Ahmed. “So, we decided to leave before they took us somewhere we did not know."

Ahmed and his family were able to pack up and take a few of their belongings with them—unlike some people in other parts of the country.

"We gathered together and left around 3 a.m.," says Ahmed. "By daybreak, around 8 a.m., we were already at the military checkpoint and screening point before entering Pulka [about nine miles from the Cameroon border]."

People flee as fighting intensifies

People continue to arrive in Pulka from surrounding villages in the Gwoza region almost daily. Many of the people arriving were trapped for years, unable to leave their villages, as a result of the conflict. Some managed to flee in the middle of the night while others were picked up by soldiers during operations. More than 11,300 people have arrived in Pulka since the Nigerian military intensified its operations in December 2016.

“[In February] I came with my daughter from Barawa because of the insurgency," says Asha*, a woman whose father was taken by Boko Haram and killed about a year ago. "I spent three days on the road with my daughter strapped to my back. It was difficult to keep up with the other people we were traveling with. I had to keep walking because they would not wait for me to rest.”

Those arriving say it is a struggle to survive in the places they have come from. There are no functioning hospitals or markets because they have been burned down or demolished, and farming activities are limited. As a result, many people arrive in poor condition, weak and hungry, sometimes needing to be carried in handcarts. Many of the children have conjunctivitis.

More assistance is needed

It is estimated that more than 42,000 people are now living in Pulka, mostly internally displaced people from surrounding areas, refugees returning from Cameroon, and the host community [who were unable to flee when Boko Haram attacked the town].

The security situation in the town is still volatile, and movements in and out are highly regulated by the military, meaning that people are unable to travel very far to farm or fetch firewood. Residents largely depend on food distributions by the government or nongovernmental organizations. However, despite these distributions, the lack of firewood and its high price means that people often go days without eating.

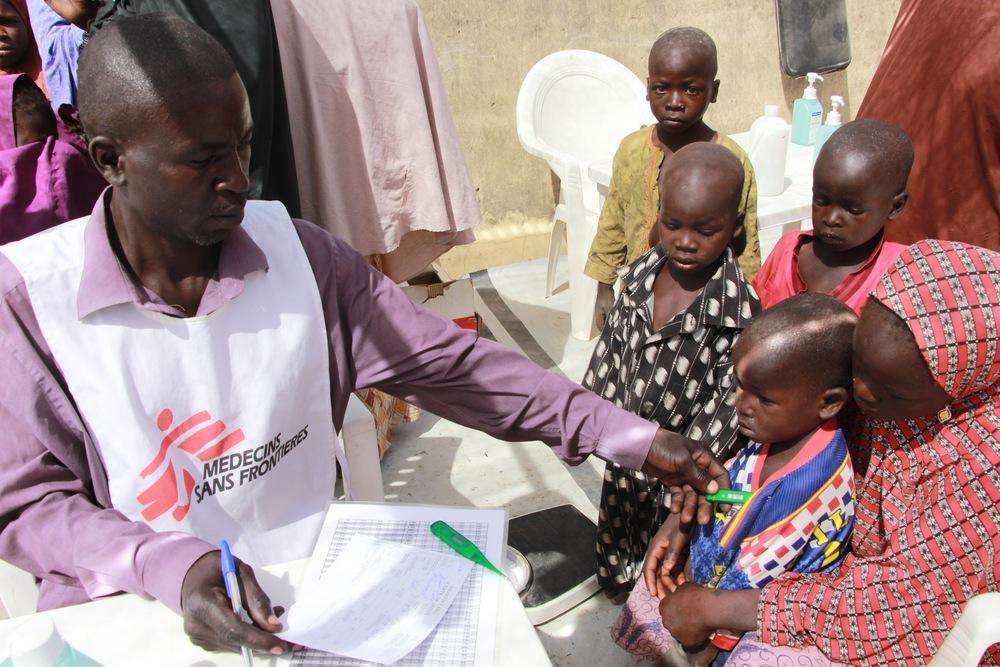

There is a limited presence of humanitarian organizations in Pulka, and, as people continue to arrive almost everyday, the infrastructure—especially health care and water—is under a lot of pressure.

*Names have been changed