This month marks the end of my third term as a member of MSF-USA’s Board of Directors and my fourth year as president.

It’s been a very rewarding time, but I’m looking forward to my departure in one respect: While I was able to do short missions in Syria, Afghanistan, Central African Republic, and South Sudan during my tenure on the board, I can now go back to the field for longer assignments, to do more of the work I find so compelling and gratifying.

MSF-USA’s board is different than most. Members are elected by MSF-USA’s Association, which is composed mostly of returned volunteers. Most have extensive field experience as well, and many of us continue going to the field during our terms.

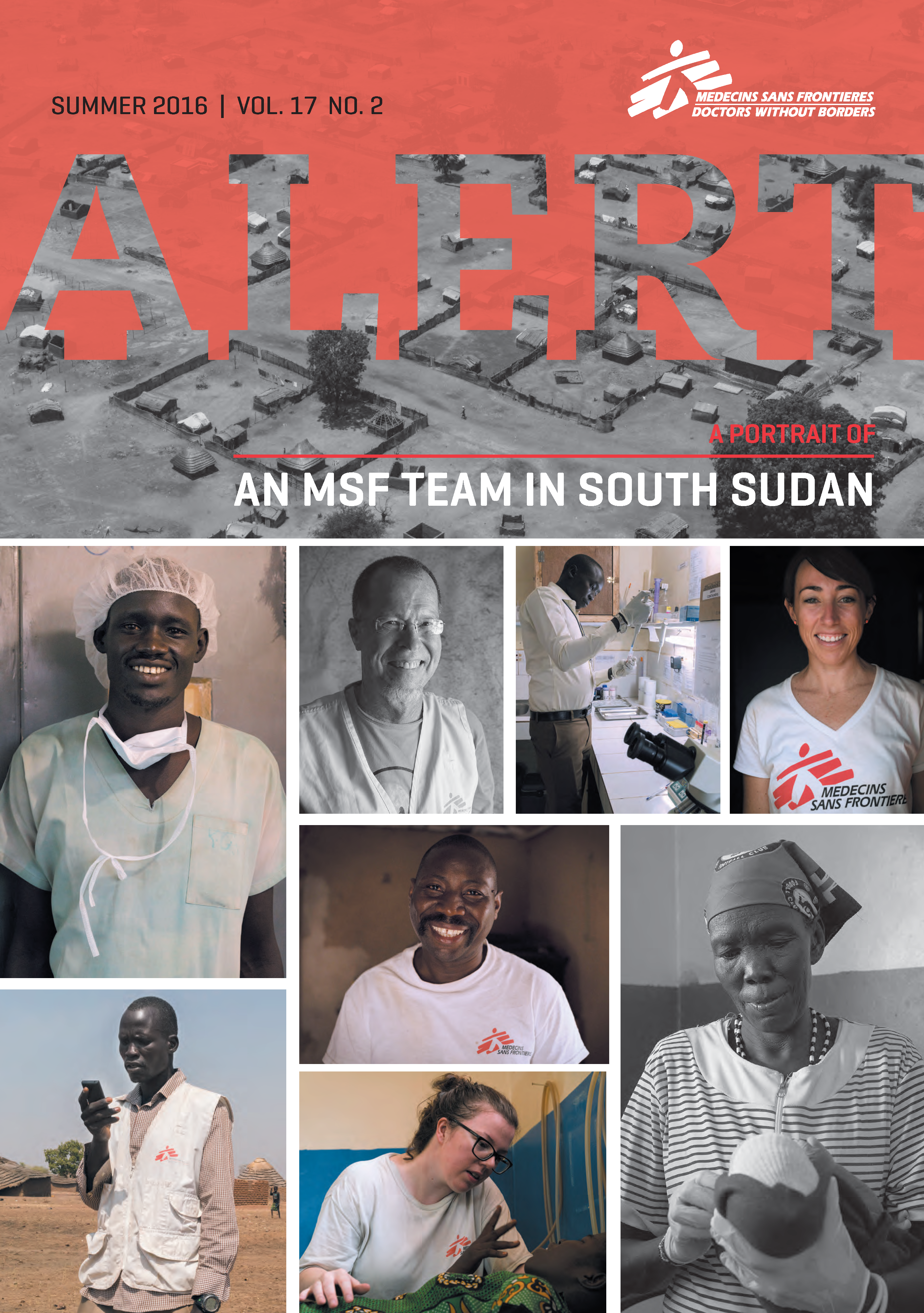

This insures adherence to MSF’s founding principles by helping to maintain a deep connection to our mission at every level. Everyone knows our primary focus is the delivery of quality health care to people who cannot otherwise access it. Everyone knows, in other words, that it’s all about the work in the field. And in this issue of the Alert, we want to give you a close-up look at life in the field by bringing you inside our hospital in Aweil, South Sudan.

I worked in Aweil in 2011 as an anesthesiologist, and I returned this past winter as the medical referent. It’s a fascinating project, a full-service hospital in a generally stable environment, so we send a good number of “first mission” field workers there. With my medical experience, I could help the teams provide care, particularly surgical care, every day. I could also, given my role on the board, gather information and listen to the concerns and ideas other staff members had, reporting it all back to the MSF-USA board and our various headquarters offices when my assignment was complete. I’ve learned over the years to see which problems are unique and which are endemic, which solutions are innovative and which have been tried before. What’s more, while first mission field staff might lament the lack of resources, I can help them see that they are doing an extraordinary job saving lives given the circumstances. There have been changes in the field over the years, which is a good thing.

MSF is no longer a small band of doctors dispatched to remote places, disconnected from the rest of the world. We are now more professional (though no less passionate) and more connected (but not less cohesive). We have far more access to information and therefore more evolved expectations and capacity. The scope of our practice has expanded and improved as well.

We use tools, like ultrasound, that improve our diagnostic capacity, recognize antibiotic resistance is not only a first world problem, and demand quality medicines for our patients to treat not only infections but also, increasingly, chronic diseases. We leverage our experience to publish scientific papers and carry out clinical trials, so that others can benefit from what we’ve learned. When we have questions and clinical dilemmas, we can Skype with headquarters staff or access the MSF telemedicine site to get consults from experts around the world.

Another change: a far greater recognition of the importance of national staff. Back in 2011, it was nearly impossible to find competent local staff in Aweil. This was a young country born out of some 30 years of civil war, after all. Now, South Sudanese men and women comprise 90 percent of the nurses, midwives, logisticians, and administrators in Aweil. We have South Sudanese supervisors. Our team even included a South Sudanese doctor, and she is terrific. The international staff supports the national staff, not the other way around. And that makes sense, because we come and go at six- or nine-month intervals. The project’s success and continuity depends on them.

Increasingly, we see national staff becoming international staff, too, serving in missions far from their homelands. This is great because having a diverse human resources pool allows us to better adapt to the needs and risks we face. It also enriches field life, enables deep cross-cultural friendships, and generally broadens the world view of all involved.

I could say more but I’ll leave with a final thought: I, like many who’ve worked in the field with MSF, have been complimented for “selflessness” because I’ve continued to work in challenging, sometimes dangerous contexts. But there is nothing selfless about my choices. The rewards of the field more than compensate for any discomfort I’ve ever experienced. It’s my great privilege to represent and help lead this organization—and I’m terribly excited to get back to the field. I think this issue of Alert will help you understand why. On behalf of the organization and myself, thank you, as always, for your support.

Sincerely Yours,

Deane Marchbein

President, MSF-USA Board of Directors