An interview with Olivia Gayraud, MSF Head of Mission in Port-au-Prince

An interview with Olivia Gayraud, a French emergency nurse, who helped open the Doctors Without Borders/Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) 56-bed emergency medical and surgical program at St. Joseph's Hospital in Port-au-Prince in October 2004. In March 2007, she became head of mission at the project, which now inlcudes a program to treat victims of sexual violence with medical and mental health care.

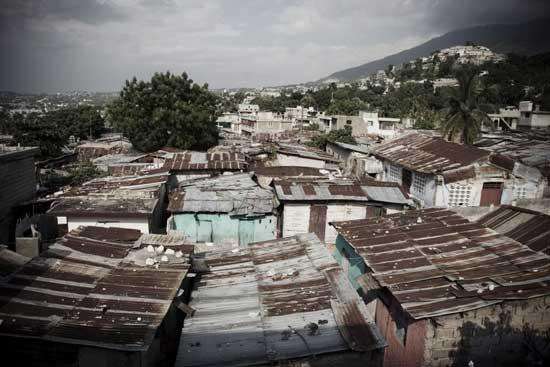

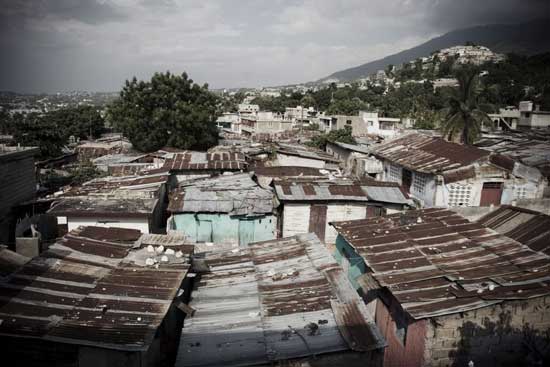

One of Port-au-Prince's impoverished slums. Haiti 2007 © Cristina De Middel

Olivia Gayraud, a French emergency nurse, helped open the Doctors Without Borders/Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) emergency medical and surgical program at St. Joseph's Hospital in Port-au-Prince in October 2004. The 55-bed program subsequently moved to the city's Trinity Hospital in December 2006, and this past March, Gayraud became head of mission at the project, which includes medical and mental health treatment for victims of sexual violence.

Between January 2005 and August 2007, the program treated 557 women for rape, many of whom were subjected to additional horrors. About 68 percent had more than one attacker; roughly 28 percent had been beaten; at least 14.5 percent had been robbed; and about 6 percent were kidnapped.

Women who survive these ordeals can be left deeply shattered, both physically and emotionally, says Gayraud, and many never seek treatment of any kind. She and her team are trying to find new ways to reach more of these women.

How has the sexual violence project in Port-au-Prince grown and changed since 2004?

MSF provides physical rehabilitation and mental health counseling in this house in the Pacot neighborhood of Port-au-Prince. Haiti 2006 © Kevin P.Q. Phelan/MSF

In December 2004, we opened the mission to respond to the high level of violence in Port-au-Prince—especially bullet injuries. In the trauma center, we provided emergency surgical care for bullet injuries and people hurt in car accidents and domestic accidents. Very quickly, maybe within one or two months of the opening of the center, we started to offer care to sexual violence victims. We started very slowly; it is difficult to do this in a city with an estimated population of two million. And, as in any country, stigma is a major obstacle to accessing rape victims.

The first year, we got an average of nine sexual violence victims per month which is very low. The second year, in 2006, we got 19. And in 2007, so far, we are getting 26 per month. So, now we've got more patients, but we think there are still more. There are other health centers that are able to take charge of such victims, but we think there are still many of them who are not seeking care.

"There are two big changes at the moment: more victims are kidnapped and the majority are beaten. The attackers seem even more perverse and more dominating."

We plan to start working outside of the area where we are located and use community workers to care for those victims. We will focus on the slums, but also on other parts of the city because the threat of violence is not only inside the slums.

And now, MSF has a new structure dedicated to the sexual violence program.

We opened it at the end of May. It's a complete facility with four beds for in-patients. We started hospitalizing victims a long time ago, but they were in the rehabilitation center with the other victims and we wanted to give them privacy and make them very comfortable. The beds could also be used by patients who were kidnapped.

We have a team of international and national staff: two midwives; two psychologists; one gynecologist; and one doctor, each of whom is available when needed; a field coordinator; a social worker; a community worker; and a receptionist.

We stress that victims of rape must come here for treatment within 72 hours after the attack so they can receive prophylactic antiretroviral treatment to reduce the risk of transmission of HIV, and antibiotics against other STDs.

How many victims come to the center within that 72-hour time frame?

Patients wait outside of an MSF clinic in Port-au-Prince. Haiti 2006 © MSF

Of the 500 victims we have received since the beginning of the program, nearly 70 percent came within 72 hours. It's relatively good and we are getting better each month. This is in part because of better outreach and coordination between MSF, other NGOs, and other facilities. Previously, there was little coordination about it at all, so the people didn't know to do this.

What happens when a woman comes to MSF after she's been raped?

They receive medical and psychological care, and they are offered follow-up treatment. Some cases need to stay a few days or a few weeks at the center. It could be for different reasons: for protection; or because the girls have been injured; maybe she's been mutilated and has been through the operating center for surgical treatment; or they are so traumatized, it's better to keep a very close watch over them.

Others return for medical and psychological consultation one or two times or longer. In fact, the majority take a few weeks to recover. The team says that over time, they can see the difference when a woman continues to come for consultations. She starts to take care of herself, to smile, and we can see that the program is very important to them.

Some victims, after receiving medical care and psychological services, need still more help. They have lost their business, all of their means, during the attack, and find it difficult to start their lives again. For these victims, we have just set up a new program. A small team at the hospital tries to find solutions for those who are not able to go back to their home or need to have some help to set up again their little business. Some of them might be out on the street, and it was important for us to be able to respond to that.

Victim Statistics

From January 2005 to June 2007, the center treated 500 rape cases.

Rape victims under 5 years old: 2%

5 to 12 years old: 10.6%

13 to 18 years old: 27.5%

19 to 45 years old: 56.5%

Over 45: 4.2%

- For 67% of victims, their attackers were unknown.

- For 46%, there were between two and four attackers.

- For 22%, there were more than five attackers.

- 66% of the victims were threatened with guns.

Are many of these victims also kidnapped?

A big change at the moment is that more victims are kidnapped (of the 557 patients MSF treated between January 2005 and August 2007, 33 were kidnapped; 15 of the kidnappings occurred in the last eight months), which makes the attackers seem even more perverse and more dominating.

The majority of victims are beaten with stones, burned with cigarettes, things like that. Often, groups are going inside a house during night and they steal everything from the family. They tie up the grandfather, father, son, everybody. And they rape the old woman inside the house. It could be a grandmother, or young women. And they force the men to look. We are seeing this a lot at the moment.

After being a victim of a rape, how are women treated in society in Haiti?

In any society, anywhere, rape is an extremely traumatic experience. Here is no exception and in fact, it's quite difficult. The victims usually prefer to hide the aggression. They are ashamed; there are parts of the culture here in which social myths around rape are very deep. But in the last few months, we have seen some small signs of change. We have a few cases who have sought justice, and their situations have been presented by the media as crimes. So I think it's quite good. But it's still difficult for many girls. I think they are afraid and when they hide themselves and the family hides them, they are sent to the bush and afterwards it's a problem to find the girls. In one case, there was information on a mass rape and afterwards I was coming, but the family had already sent all the girls outside Port-au-Prince.

"The team says that over time, they can see the difference when a woman continues to come for consultations. She starts to take care of herself, to smile, and we can see that the program is very important to them."

What other challenges do you face in running this kind of treatment program in Haiti?

Well, I think now the program is running well, but we could treat more patients. We are going to set up a mobile team that will hopefully allow us to provide more help. Also, we have set up a free phone line, a hotline, to receive calls from victims of sexual violence, kidnapping, and other aggressions. They can call MSF during the day and we will give them information and make appointments. We will set this up in different areas of the city, and we need to give the information often, I think it's something we need to inform the population of every day because if you are victim, maybe you won't listen at first.

Olivia Gayraud started with MSF in 1998 and has worked in Afghanistan, Burundi, Chad, Democratic Republic of Congo, East Timor, Georgia, Ivory Coast, Madagascar, Niger, Sri Lanka, Sudan, and Uganda.

MSF also operates a 75-bed primary health center in Cité Soleil's Choscal Hospital and a health center in Chapi; provides support to health structures in Petite Riviére focussing on maternal and child health; and operates the 60-bed Jude Anne Hospital in Port-au-Prince's Delmas area, where women who have little access to health care are targeted.