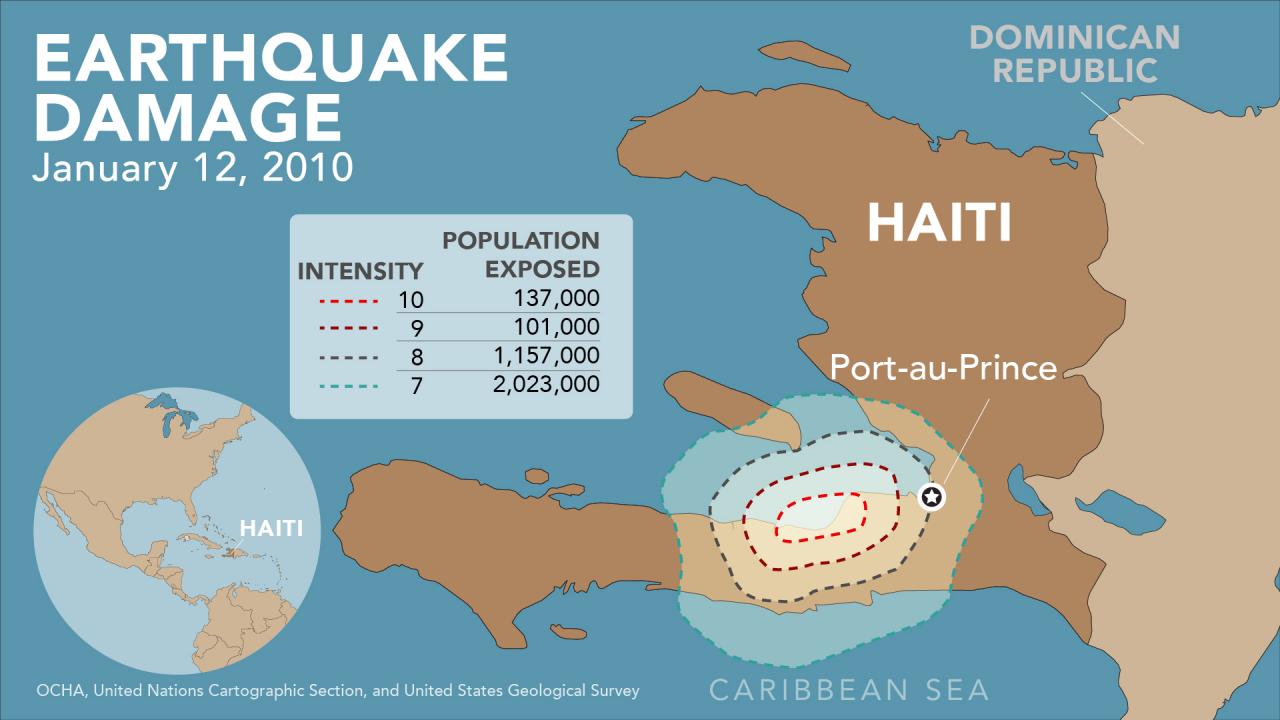

The immediate effects of the 2010 earthquake in Haiti

In a single day, 60 percent of Haiti’s already fragile health system was destroyed. Ten percent of the country's medical staff were either killed or left the country in the following weeks.

Tending to massive needs

Because of our rapid-response logistical capacity, we were able to quickly send an additional 2,600 MSF staff members to provide lifesaving care throughout impacted areas.

In what would become one of our largest-ever emergency responses, we delivered nearly 1,200 metric tons of supplies—including everything from an inflatable hospital to medications, dialysis machines, and bandages—to Haiti in the first seven weeks after the earthquake.

Within ten months of the earthquake, we treated more than 358,000 people, performed more than 16,500 surgeries, and assisted more than 15,000 births.

Adapting to the needs in the years following the earthquake

The massive humanitarian response helped expand Haiti’s medical capacity. In the following years rubble was removed; new, earthquake-resistant structures were built; more staff were trained; and stocks and availability of medical supplies temporarily improved.

Ongoing challenges happening in Haiti

But the response to the earthquake also brought its share of challenges. There were numerous accounts of foreign “experts” failing to take the needs of Haitian people into account, misuse of aid and local corruption, abuses by aid workers, funding promises not kept, and the introduction of cholera by United Nations peacekeeping forces.

MSF was not exempt. We struggled to launch some longer-term projects and had to close temporary projects to focus on emergencies in other parts of the world. At the same time, MSF addressed some specific unmet medical needs, such as emergency and trauma care, treatment of burn victims, responding to epidemics and natural disasters, and, until recently, emergency obstetric and maternal care. Doing so we moved many of our activities from temporary structures to more permanent ones.

Cholera

In October 2010, barely 10 months after the earthquake, a cholera epidemic broke out north of Port-au-Prince. The disease rapidly spread to other parts of the country, including the capital. By the end of 2011, an estimated 520,000 people had contracted cholera and more than 7,000 people had died.

From 2010 to 2016 MSF treated more than 300,000 people with cholera symptoms in the country, with a peak in 2011 when we treated 170,000 patients in 50 facilities. After it was disclosed that cholera had been inadvertently brought to the island by a United Nations (UN) battalion from Nepal, many of the people affected by the disease requested certificates proving they had been treated in hopes of receiving compensation from the UN. In response, MSF set up dedicated teams to provide thousands of former patients with medical certificates.

Emergency and trauma care

Even before the earthquake, Haiti had one of the highest rates of maternal mortality in the western hemisphere. MSF’s emergency obstetric hospital in Port-au-Prince was damaged during the quake. After providing assistance to the Ministry of Health maternity hospital, Isaïe Jeanty, in 2011, MSF opened the Centre de Référence des Urgences Obstétricales, a hospital in Port-au-Prince for women with obstetric complications and newborns requiring specialized treatment. Before the hospital closed in July 2018, our teams cared for approximately 120,000 women and assisted more than 40,000 births.

In the South Department, MSF supports the Ministry of Health in the delivery of primary health care, focusing on mother-and-child care and treatment of waterborne diseases. MSF started supporting Port-à-Piment health center in October 2016. In 2019, we rehabilitated and started supporting two more health centers in Côteaux and Chardonnières. Based on the growing needs in this rural area, MSF will extend its support to six health centers and a referral hospital in the South Department in 2020.

Burns treatment

Shortly after the earthquake, the number of patients with severe burns—a widespread problem in Haiti linked to poor housing conditions—increased. While burn victims were initially treated at the St. Louis inflatable hospital, these services were transferred to a semi-permanent structure near the Cité Soleil neighborhood in May 2011.

In 2018, MSF completed the construction of a new hospital in Drouillard, with better facilities designed for improved infection control, a major issue in burns treatment. In four years (until the end of November 2019), our teams cared for 2,614 people with burn injuries, at an average of 650 to 700 patients per year. Ninety percent of them came from the Port-au-Prince neighborhoods of Cité Soleil, Croix de Bouquets, Delmas, Martissant, and Carrefour. To this day, Drouillard is the only facility in Port-au-Prince specialized in caring for patients with severe burns.

Victims of sexual and gender-based violence

Haiti has long been plagued by high levels of sexual violence, and its incidence continued to be underreported—and under-addressed—in the years following the earthquake. Recent surveys in Haiti found that 20.4 percent of women who had ever been married had experienced physical or sexual violence inflicted by an intimate partner and that 13 percent of women overall had experienced sexual violence by any perpetrator. Women are not the only victims. Another survey in 2014 found that 25.7 percent of Haitian women and between 21.5 percent and 23.1 percent of men had experienced child sexual abuse.

In May 2015, MSF opened Pran Men’m clinic (Haitian Creole for “take my hand”) in Port-au-Prince to provide medical and psychological care and guidance on social and legal support to victims of sexual and gender-based violence. We also support the Haitian Ministry of Health in the care of survivors at Haiti National University Hospital and Henri Border. Since 2015, our teams have supported more than 4,500 survivors of sexual violence.

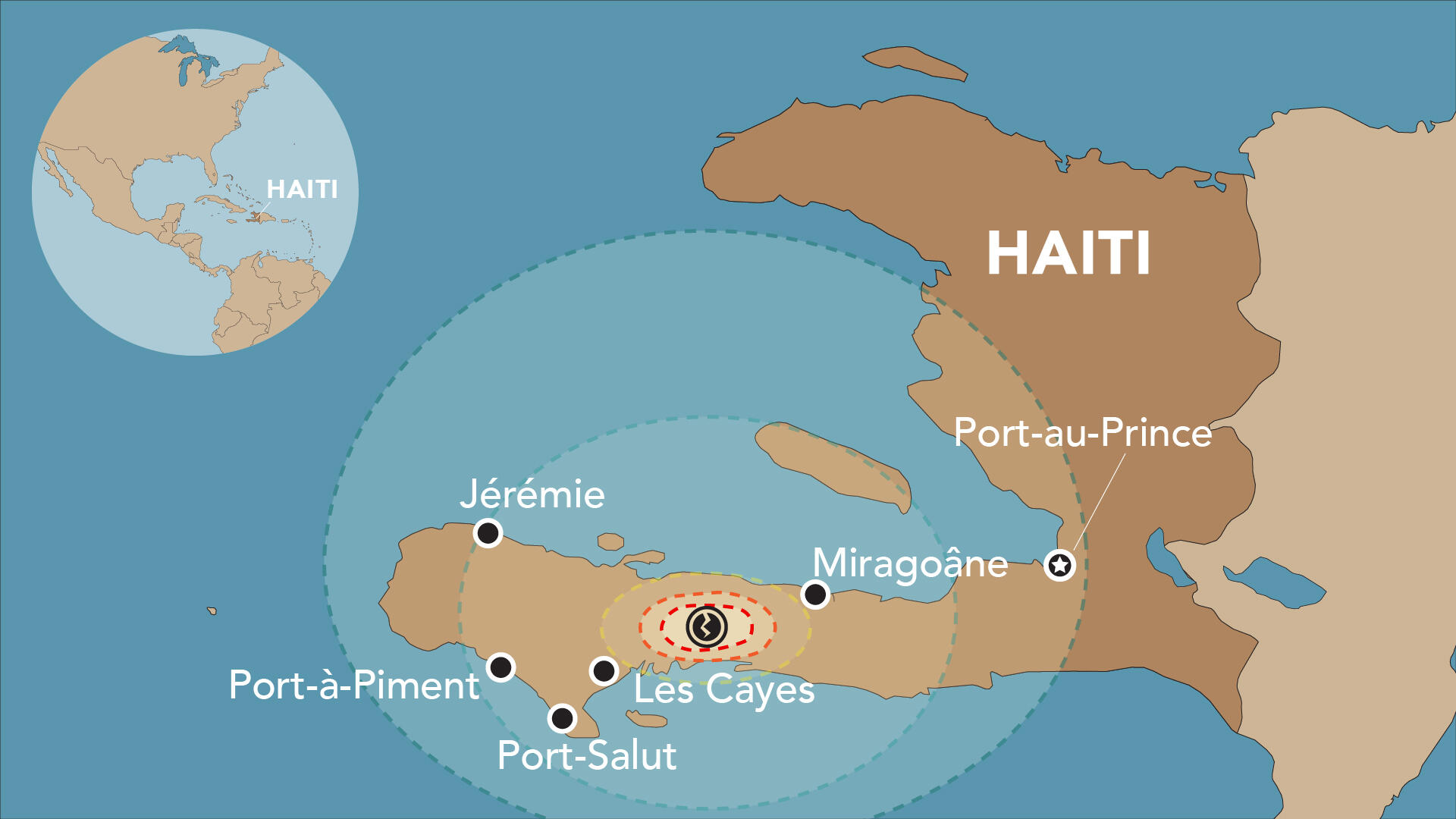

Hurricane Matthew

On October 4, 2016, Hurricane Matthew hit Haiti. The category four hurricane—with winds up to 145 miles per hour—once caused widespread destruction. In the aftermath, MSF provided care to more than 6,000 people impacted by the storm and provided over 10 million liters of clean water to help prevent further cholera outbreaks.

What's happening in Haiti now?

Since July 2018, a deepening political and economic crisis has once again put access to health care in Haiti in jeopardy. While thousands of demonstrators have taken to the streets to protest skyrocketing prices of goods, a lack of economic opportunities, and government misuse of funds, the international community has mostly remained silent.

According to the World Bank, more than six million Haitians—about 60 percent of the population of the country—live below the poverty line on less than $2.41 (US) per day, and more than 2.5 million fall below the extreme poverty line of $1.23 per day. This means that most families struggle to buy food or pay for medicines or medical care.

The uncertainty and unrest have also led to an increase in violence. In the first two weeks after reopening our trauma center in Port-au-Prince, more than half of the patients we saw were victims of gunshot wounds.

In 2020, as the coronavirus pandemic hit Haiti, MSF converted its Drouillard burns hospital into a COVID-19 treatment center before returning it to its original purpose after the first wave passes.