Since the global coronavirus pandemic began, Doctors Without Borders/Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) has had two priorities: First, to keep existing essential medical services up and running for the hundreds of thousands of patients who rely on us; and second, to prepare for and respond to the spread of the virus itself.

Faced with unprecedented challenges, our teams—like health care workers everywhere—have had to quickly adapt to the new realities of a world changed by COVID-19 at a time when lockdowns and travel bans are restricting the movement of both medical staff and supplies.

“The challenges have been immense and we’ve adapted our entire way of working,” said Brice de le Vigne, head of MSF’s COVID-19 taskforce. “As a global humanitarian organization, our surge capacity during emergencies is normally built on being able to move specialist experienced staff and medical supplies around the world at a moment’s notice. But with travel restrictions, lockdowns, and unprecedented disruptions in the global supply chain of essential personal protective equipment, medicines, and medical materials, our teams have been pushed to find solutions beyond our usual way of operating to be able to continue caring for patients.”

Devastating knock-on effects

While the world’s attention is understandably focused on the direct impact of COVID-19, in many of the places where MSF works—where health systems are already fragile and people often live in extremely precarious conditions—the pandemic’s indirect impacts could also be catastrophic.

“Getting the pandemic under control is clearly a priority for everyone, but it was never an option for us just to drop our regular medical services and focus solely on COVID-19,” said Kate White, who serves as medical focal point for MSF’s COVID-19 taskforce. “We know from decades of experience in other outbreaks that the knock-on effects on the rest of the health system can be just as, if not more, devastating than the disease itself. Keeping essential health services available and accessible is vital to prevent losing even more lives, whether from malaria, measles, malnutrition, or complicated pregnancies.”

The COVID-19 pandemic risks further reducing many vulnerable people’s already limited access to health care, as resources—both human and financial—are diverted from regular health care to the COVID-19 response. Health services may be downsized or shut down to limit the risk of transmission, vital vaccination campaigns may be canceled, and frontline health care workers may fall sick or die in places where there were already too few medical staff to meet the needs.

Fear of infection

At the same time, people may put off seeing a doctor for any number of deadly medical conditions due to the difficulty of moving around during lockdowns or out of fear of becoming infected with COVID-19 in a health facility. MSF teams have already seen a significant decrease in the number of patients coming to our facilities—in some cases by up to 50 per cent—in projects in Bangladesh, Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), Afghanistan, Nigeria, Sierra Leone, and Egypt.

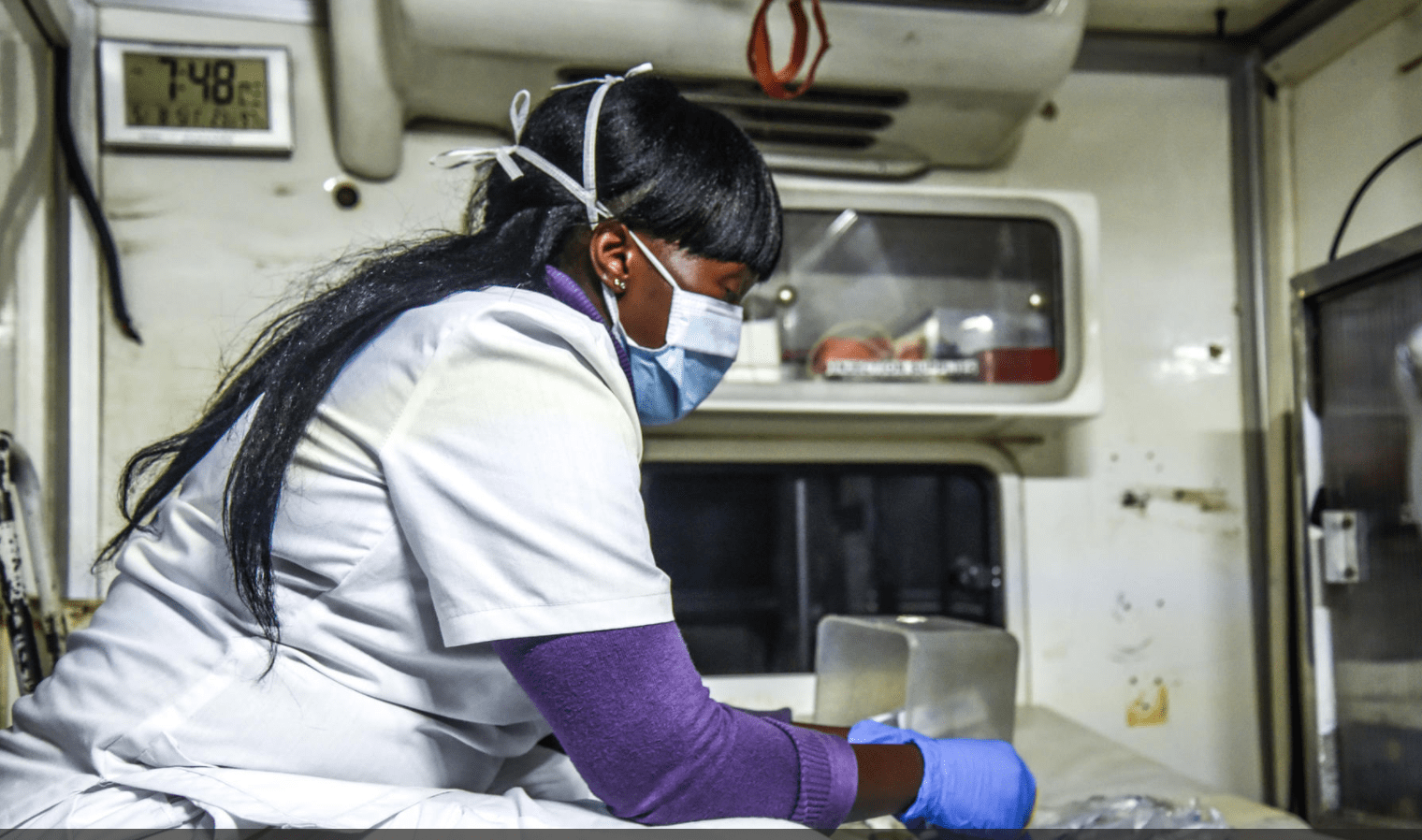

In order to ensure that health facilities are safe places for staff and patients and become part of the chain of transmission, MSF has implemented specific COVID-19 infection prevention and control measures in all our clinics and hospitals, and has supported health authorities in many countries to do the same in their facilities.

“In many places where we work, the MSF hospital or clinic might be a community’s only option for essential health care for hundreds of kilometers,” said White. “People need to be able to trust that when they come to us—whether they are unwell with COVID-19, want to get care for their child with diarrhea or malaria, or safely deliver their baby—they won’t come to more harm than if they hadn’t come to us in the first place.”

Beyond the hospital walls

At the same time, MSF teams in some 450 projects in more than 70 countries around the world are looking beyond hospital walls and adapting medical activities to the specific needs of the communities where we work. While COVID-19 is certainly on almost everyone’s mind, it may not necessarily be the top priority health issue everywhere.

“A cookie-cutter approach won’t work in this pandemic,” said White. “We have to engage with communities to understand what their concerns are and adjust our activities in ways that both meet their most pressing health needs and simultaneously reduce the risks of COVID-19 transmission. It’s pointless if we try to roll out a perfect COVID-19 service, but it’s actually peak malaria or malnutrition season and that’s the main cause of sickness or death in that community.”

Insurmountable challenges and heartbreaking decisions

Unfortunately, in some cases, the obstacles to continue providing care are currently insurmountable. In Syria, El Salvador, Malaysia, and Mexico, MSF teams have had no choice but to temporarily reduce or suspend mobile clinic activities. In Iraq, we have halted admissions of new patients into our noncommunicable diseases program; in Monrovia, Liberia, we were forced to suspend pediatric surgeries due to staffing shortages caused by travel restrictions; in Pakistan we have suspended cutaneous leishmaniasis consultations in Balochistan and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, as well as temporarily closed a maternity hospital in Peshawar; and in Zamfara, Nigeria, we have temporarily closed most of our activities responding to lead poisoning associated with mining work.

With such uncertainty about our future capacity to guarantee a consistent supply of international staff and medical supplies, including personal protective equipment, all new planned initiatives have been put on hold. This includes the opening of a new maternity and pediatric facility in Qanawis, Yemen, where women and children continue to suffer the impacts of years of grinding conflict.

Finding creative solutions

Around the world, MSF teams have been working to find creative ways to keep health care accessible during the pandemic and support frontline health care workers as they care for their communities. There have been some remarkable initiatives, from increasing the availability of telemedicine to providing online infection prevention and control trainings for nursing home workers to running health promotion campaigns on social media to managing WhatsApp groups of traditional healers.

In an effort to reduce the chance of transmission we have reduced by half the recommended number of antenatal consultations for pregnant women in our clinics. In our maternal health projects in countries including Nigeria, DRC, Sierra Leone, and Bangladesh, we are ensuring that women can still receive the care they need by engaging with trusted people in their communities, such as local health workers and traditional birth attendants, to identify when a woman needs to go to hospital because of complications.

In our HIV, tuberculosis, hepatitis C, and noncommunicable disease projects in countries as diverse as South Africa, Ukraine, Pakistan, and Cambodia we have reduced routine consultations and distributed essential drugs to patients for longer periods (one to six month supplies, depending on the person’s health condition) so that they do not have to visit a health facility as often. At the same time, we are ensuring that patients receive follow-up through phone consultations, messaging apps, and peer support networks.

Among the most at-risk for COVID-19 complications are people with underlying lung disease such as multidrug-resistant tuberculosis (MDR-TB). In Eswatini, an MSF team is reducing risks for these vulnerable patients by bringing care closer to their homes and limiting risky unnecessary to health centers via public transportation. The majority of our 40 MDR-TB patients now use “video observed therapy,” using smartphones distributed by MSF to film themselves taking their medication and send the video to be checked by a nurse.

Meanwhile, many of MSF’s mental health services, including in El Salvador, Palestine, and India now offer telephone hotlines for both new and existing, while counselors and psychologists provide consultations by phone. In Kashmir, where the COVID-19 lockdown has prevented MSF teams from running in-person mental health clinics, clinical psychologist Ajaz Ahmad Sofi says phone counseling has actually opened up the service to many more people. “Many of my new patients say that they have been avoiding visiting a counselor because of a fear of being seen by relatives, neighbors, or friends around the clinic. So while the lockdown has made lives much harder, in a way it has enabled more people to seek help, while allowing us to continue to provide a much-needed medical service.”